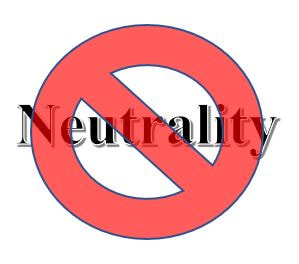

"Good Enough" is an Equity Issue “Good enough.” We have probably all heard it. We may have even said it. While these words may seem innocuous in the moment, a closer look can reveal an underlying equity issue. Most of us have limited resources, including time. Even though limitations impact our actions, we still have a choice. Whenever we settle for “good enough” instead of challenging ourselves and the systems and structures around us, we perpetuate inequities. A “good enough” attitude inhibits our abilities to maximize the resources we have and to provide opportunities for the best possible outcomes for all students.  Multiple factors can influence our willingness to accept (or even promote) “good enough” thinking. We may feel pressured by curricula, time constraints, and evaluation systems. We may also feel held back by a lack of understanding, inadequate development, shrinking budgets, or continually changing initiatives. Each of these concerns may seem important or insurmountable in the moment, but what ongoing issues truly underlie a “good enough” attitude?  We need to begin with our conceptions of education. We can approach education as something we do to students or as a process that occurs with students. Drawing from Paulo Freire’s (1970/2017) criticism of the banking model of education, approaching education as something we do to students (making deposits of knowledge without building capacity) allows for justification of “good enough” based on our biases and (mis)perceptions. When education is viewed from the banking perspective, the system decides the endpoint, even if the end is just “good enough” to maintain the status quo.  In his book The Miseducation of the Negro, Carter G. Woodson (1933/2018) also noted a good enough manner of educating People of Color in the United States. One of the many take-aways from Dr. Woodson (1933/2018) is the “mis-education” that discouraged further development of talents or skills of Students of Color. Further training to develop particular talents or skills was often considered unnecessary and consequently inhibited. Similar to Freire’s (1970/2017) banking education concept, Woodson (1933/2018) places teachers and administrators in an influential role that can end educational pursuits at “good enough.” While the ideas forwarded by Freire (1970/2017) and Woodson (1933/2018) may be critiqued as historical perspectives, we unfortunately do not have to dig deep to see the relevance in current educational systems (Kendi, 2019; Love, 2019). This is not to say that all teachers and administrators intentionally foster attitudes that are biased or limiting, but they nonetheless further them. In many ways, educators are, as suggested by Woodson (1933/2018) and Kendi (2019), products of the system. As such, all educators need to be aware of the influences of these systems and our roles in them.  The actions of educators can maintain inequitable systems. At its best, a “good enough” approach represents a neutrality that does not challenge individual beliefs or larger systems. When educators settle for good enough and remain neutral, we do not leverage our privilege or expertise to advocate for necessary changes. Without meaningful and sustained challenges to inequitable, unjust, biased, and racist systems, oppression continues.  While the neutrality of a “good enough” approach may passively allow inequitable systems to continue, “good enough” can become a force that expands systems of oppression and resists efforts for equity and social justice. Educators may employ “good enough” thinking to deny access to opportunities in the classroom, whether through individual actions or restrictive curricular pathways. Biases can be manifested as lower expectations or attitudes that discourage and limit student ability to engage in deeper learning. Depending as the context, “good enough” can move from passive neutrality to active oppression. As educators, we cannot settle for “good enough,” whether passively or actively limiting our students. Yet, we also know we are products of an unjust system. This leads to questions surrounding action to move beyond “good enough” thinking and systems. How can we, as products of the system, change our thinking, our actions, and, ultimately, the unjust systems of which we are a part? What steps can we take to ensure all students have access to equitable education that is not just “good enough”?  Keeping in mind the bigger systems, we can begin with self-reflection and learning that can prepare us to network and advocate for all students. Here are some ways to get started: 1. Develop – As Maya Angelou said, “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.” We can begin to overcome “good enough”, discriminatory practices by learning, by knowing better. This is a process that includes not just gaining knowledge, but also critical self-reflection on beliefs, thoughts, words, and actions. It is up to each of us to take responsibility for our own growth. Here are several recent publications to help further personal development: How to be an Antiracist by Ibraim X. Kendi We Want to Do More Than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom by Bettina Love Science in the City: Culturally Relevant STEM Education by Bryan A. Brown There are also platforms on social media that can aid in personal and professional development. Here are two Twitter handles to help get started (check out who they follow to learn more): @ClearTheAirEdu #cleartheair @Tolerance_org (Teaching Tolerance) 2. Collaborate – After taking the step that includes learning and serious, critical self-reflection, we need to make appropriate changes in our lives, both personal and professional. As we undertake the process of necessary shifts in our thoughts, beliefs, words, and actions, it may be beneficial to have a network of people that support our work. This support can take many forms and may range from organizations, online social networks, and individuals recommending resources to aid in continued development to people in our lives that are willing to constructively point out our mistakes and allow us to continually grow. A network of knowledgeable and reliable people will provide for collaboration that supports and maintains accountability. While the feedback we receive may not always be pleasant, it is essential for achieving the necessary, antiracist outcomes. 3. Lead – Depending on the context, our personal and professional growth may or may not be well-received. Regardless, moving from “good enough” to equitable, antiracist practice and policy offers opportunity to lead. Educators can foster classroom-level changes that set positive expectations and create environments where all students can learn. Beyond the classroom, educators should be advocates, abandoning neutrality that maintains unjust, “good enough” systems. Remembering the lessons from Freire (1970/2017), we need to create spaces and conditions that do not overpower or coerce the voices and actions of the oppressed to conform to current conditions. Instead, we need to allow these voices to be heard and understood in an effort to drive the change necessary to fundamentally alter oppressive conditions. Advocating for change may be difficult and uncomfortable, but we must move past the discomfort and lead through advocacy that centers the actions and voices of those that are oppressed. It is these changes that can move us from “good enough” to the best we can be! References Brown, B. A. (2019). Science in the city: Culturally relevant STEM education. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard Education Press. Freire, P. (2017). Pedagogy of the oppressed (Myra Bergman Ramos Trans.). London, England: Penguin Classics. (Original work published in 1970). Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. New York, NY: One World/Ballantine. Love, B. L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press. Woodson, C. G. (2018). The mis-education of the Negro. Middletown, DE: CreateSpace Independent Publishing. (Original work published in 1933).

0 Comments

|

Details

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed